Reward Weightings

Reward weightings will promote climate actions that are better for people and the planet.

— Dr. Delton Chen (Founder)

Actions to mitigate climate change are often over-simplified in the mainstream media. One problem that is often overlooked, is that climate actions frequently have side effects. For example, forests have been confiscated from indigenous communities for carbon offsetting schemes, rare birds have been killed by wind farms, and unique forests have been cut-down and chipped for biofuel. These unwanted side effects should be made transparent to the public, and they should be avoided when possible. Given that positive and negative side effects are common, climate mitigation should be seen as a trade-off problem.

How can we manage local trade-offs in a way that can be scaled globally? The approach that is proposed here is to invite stakeholders to define and rank the criteria for judging the positive and negative side effects (i.e. the co-benefits and harms) of low-carbon projects. Each individual stakeholder should be able to submit his/her ranked criteria to a stakeholder survey. The survey results should be used to find consensus on the method of evaluating the side-effects of low-carbon projects. The consensus method should be used to evaluate the side-effects and to provide a subjective score for each low-carbon project. These scores should then be used to adjust the carbon rewards higher or lower.

The reward “adjustments” are quoted in dollar terms. The sum of all of the reward adjustments for a given low-carbon project are called “net adjustments”. The net adjustments are called “reward weightings” when they are quoted in percentage terms. The operational objective of the reward weightings is to incentivise more co-benefits and fewer harms, and to create a virtuous circle for investing in low-carbon projects. Virtuous circles of investment should be established for improving (1) energy reliability, (2) community wellbeing, and (3) ecosystem health. These three issues are presumed to be the most important issues for stakeholders, but other issues may arise in the future. The following three sections provide more details on what is a reward weighting, why they are needed, and how they can be determined.

What are Reward Weightings?

Reward weightings will be used to incentivise better outcomes for people and planet.

More specifically, a reward weighting (w) is a scaling factor that is applied to a base reward (R) to calculate the weighted reward (R*) that is to be given to each enterprise that successfully undertakes a climate action:

R*= w × R

Weighted Reward = Reward Weighting × Base Reward

(Eq. 1)

Climate actions that produce relatively more co-benefits and fewer harms will result in w > 1, and those climate actions that produce relatively less co-benefits and more harms will result in w < 1. These weighting factors (w) are subjective and they communicate the relative changes in the reward payments. The weighting factors (w) will help identify the climate mitigation technologies and methods that are better for people and planet.

Although the weighting factors (w) are useful as a reporting metric, the weighted rewards (R*) will be determined using net adjustments (r), according to the following formula:

R* = r + R

Weighted Reward = Net Adjustment + Base Reward

(Eq. 2)

The reason that the weighted rewards (R*) will be determined using net adjustments (r) and not weighting factors (w), is because the calculations are greatly simplified when the adjustments are based on additions (see Eq. 2) rather than on multiplications (see Eq. 1).

The net adjustment (r) is the total of three different types of reward adjustment, as follows:

r = renergy + rcommunities + recosystems

Net Adjustment = Adjustment for Energy + Adjustment for Communities + Adjustment for Ecosystems

(Eq. 3)

where renergy is the adjustment for energy reliability, rcommunities is the adjustment for community wellbeing, and recosystems is the adjustment for ecosystem health.

The above three adjustments will be evaluated separately and then added to the base reward (R) for each climate action. A justification for why these adjustments are needed, and an explanation for how they will be evaluated, are provided below.

Why are Weightings Needed?

Reward weightings are needed to establish a ‘virtuous circle’ of financial flows into climate actions that are beneficial for people and planet.

For example, the growing demand for electric vehicles and lithium-ion batteries could have a detrimental impact on people and ecosystems where lithium, nickel and cobalt are mined. Another example is the construction of large solar farms and wind farms close to sensitive ecosystems and communities. There is clearly a need to manage these local trade-offs.

It is proposed here that the reward weightings can/should be used to guide the innumerable trade-offs, by including the preferences of key stakeholders in the price signal of the GCR. This will be achieved by inviting stakeholders to score each low-carbon project in relation to these three issues: (i) energy reliability, (ii) community wellbeing and (iii) ecosystem health.

The purpose of the reward weightings is to incentivise market participants to develop low-carbon projects that respond to the ranked criteria of stakeholders. The operational objective is to create a positive feedback loop between the reward weightings and the decisions of planners and investors. This feedback loop may be described as a ‘virtuous circle’ of financial flows into climate actions that lead to better outcomes.

How will Weightings be Implemented?

The stakeholder groups are mandated to assign scores and calculate reward adjustments for the various low-carbon projects in their domain of influence. The sum of all of the reward adjustments within each stakeholder group will aggregate to zero, according to this conservation rule:

∑ ri j k = 0 : i = 1 to L

The sum of all reward adjustments equals zero for each stakeholder group

(Eq. 4)

where i denotes the climate action, L denotes the total number of climate actions in the group, j denotes the group of stakeholders, and k denotes the issue that is being examined in order to determine a reward weighting. Note that there are only three issues to be considered by stakeholder groups: (k=1) energy reliability, (k=2) community wellbeing, and (k=3) ecosystem health.

There is no single “right way” to form stakeholder groups, or to find consensus on the ranked criteria, or to undertake the scoring of low-carbon projects. It is recommended that a variety of methods and systems be proposed and tested until some effective methods and systems are found. Alternatively, governments may prefer to design these methods and systems in a top-down approach, in order to express greater control over the process of determining the reward weightings. The reward weightings for energy reliability and ecosystem health may require a top-down approach because the issues are technical and require expert knowledge. The reward weightings for community wellbeing may require a bottom-up approach, because the issues are based on cultural norms and individual preferences.

Here we shall consider how the reward adjustments (see Eq. 2, 3 and 4) may be determined, using the concept of stakeholder groups. As mentioned above, there are three kinds of stakeholder group, because there are three key stakeholder issues: (1) energy reliability, (2) community wellbeing, or (3) ecosystem health.

Reward adjustments for climate actions will be determined by the groups of stakeholders that are affected by these actions.

The determination of reward adjustments will follow this five-step process:

Step 1. Individuals will organise into stakeholder groups for one of the three key issues

Step 2. Individuals within a stakeholder group will submit their ranked criteria to a survey for their stakeholder group

Step 3. A consensus will be found on each stakeholder group’s ranked criteria for evaluating low-carbon projects

Step 4. The ranked criteria will be used to create a subjective scoring system for evaluating each low-carbon project

Step 5. Scores will be assigned and reward adjustments will be calculated for each low-carbon project

Each individual stakeholder will be invited to join a stakeholder group, and then submit his/her ranked criteria in order to achieve a group consensus on the ranked criteria. The details of the consensus method are not considered here, however one possible method is called quadratic voting.

There should exist some universal guidelines for organising citizens into stakeholder groups for the purpose of improving the wellbeing of communities. For instance, the Declaration of Universal Human Rights under the United Nations, could be used to develop guidelines for creating and managing stakeholder groups for communities. These guidelines should address the issue of how to organise citizens into stakeholder groups based on their geographic location. The formation of stakeholder groups by citizens will need to take into account cultures, political borders, and the ability of citizens to interact with the policy. The end goal is to protect and support community wellbeing.

Each low-carbon project will only be associated with one stakeholder group (per issue), and so larger groups will likely have a greater influence on investment decisions because larger groups will generally be able to influence more low-carbon projects. If a low-carbon project does not associated with any of the available stakeholder groups, then the carbon reward for that action will not be adjusted because there is no need for an adjustment.

When the conservation rule is applied correctly (see Eq. 3 & 4), the reward adjustments for all climate actions should sum to zero for each assessment period:

∑ r = 0

The sum of all reward adjustments should equal zero for each assessment period

(Eq. 5)

We may look at the conservation rule another way by considering Eq. 2 with Eq. 5. If the sum of the reward adjustments equals zero, then the sum of the weighted rewards (R*) must equal the sum of the base rewards (R), as follows:

∑ R* = ∑ R

The sum of all weighted rewards equals the sum of all base rewards for each assessment period

(Eq. 6)

The conservation rule (see Eq. 4, 5 & 6) says that carbon rewards cannot be created or destroyed when adjusting the rewards, and the carbon rewards can only be redistributed amongst climate actions that exist within the same stakeholder group. This implies that the GCR policy will create a competitive market for the reward adjustments within each stakeholder group.

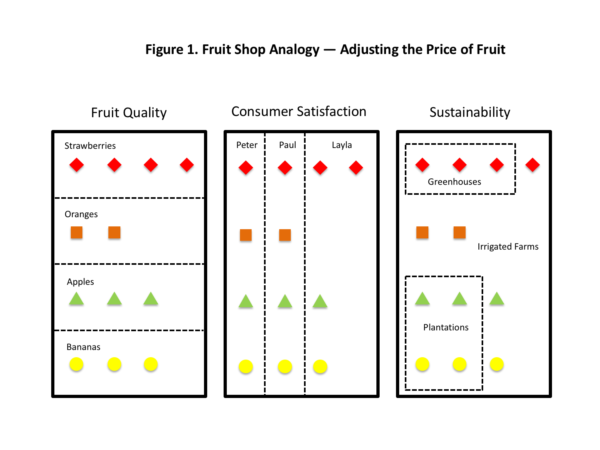

If the notion of stakeholder groups is difficult to conceptualise, then consider the fruit shop example provided in Footnote [b]. The fruit shop example involves three groups of stakeholders who are concerned with three different issues regarding the quality of fruit. The stakeholder groups are tasked with evaluating the quality of fruit, which is analogous to stakeholder groups evaluating the quality of low-carbon projects.

Let’s consider a hypothetical reward market as described in Table 1. In this hypothetical reward market there are four types of energy (methane, electricity, biofuel, and hydrogen). There are three community groups, and three ecosystems that are affected by low-carbon projects. In this hypothetical example, the various climate actions in the reward market are grouped according to the three issues and their associated stakeholders.

The authority for the reward policy will help design and oversee the stakeholder groups, stakeholder surveys, ranking systems, scoring systems, and protocols for evaluating the reward adjustments. The overall objective will be the establishment of a functional marketplace.

The technical and political feasibility of forming stakeholder groups and implementing the reward adjustments is discussed in the sections that cover: (1) energy reliability, (2) community wellbeing, and (3) ecosystem health.

Table 1. Policy for Adjusting Carbon Rewards (Hypothetical Examples)

| Key Issue | Energy Reliability (k=1) | Community Wellbeing (k=2) | Ecosystem Health (k=3) |

| Stakeholder Groups (j) | Energy markets for Methane (j=1), Electricity (j=2), Biofuel (j=3), and Hydrogen (j=4) | The communities of France (j=1), Rénunion (j=2), and Guyane (j=3) | Forests (j=1), Wetlands (j=2), and Savannahs (j=3) |

| Stakeholders | Planners, engineers, regulators and consumer representatives who are invited to provide expert advice on energy reliability in the four energy markets. | Citizens who submit their preferences on a voluntary basis. | Ecologists, biologists, and local protectors who are invited to provide expert advice |

| Scoring System | Score for the reliability of energy supplies | Score for community wellbeing | Score for ecosystem health |

| Reward Adjustments | ri,j,k | ri,j,k | ri,j,k |

Footnotes: i = the low-carbon project that receives a carbon reward, j = stakeholder group, k = key issue

Updated 1 may 2021

Footnotes

Table 2. Fruit Shop Analogy for Adjusting Prices (Hypothetical Examples)

| Key Issue | Fruit Taste (k=1) | Consumer Satisfaction (k=2) | Sustainability (k=3) |

| Stakeholder Groups (j) | The taste of Strawberries (j=1), Oranges (j=2), Apples (j=3), and Bananas (j=4) | Satisfaction of Peter (j=1), Paul (j=2), and Layla (j=3) | Sustainability of Greenhouses (j=1), Plantations (j=2), Irrigated Crops (j=3) |

| Stakeholders | Experts in fruit tasting who are invited to give advice. | Consumers of the fruit who volunteer their preferences. | Experts in sustainable agriculture who are invited to give advice. |

| Scoring System | Score for taste | Score for consumer satisfaction | Score for sustainability |

| Price Adjustments | pi,j,k | pi,j,k | pi,j,k |

Footnotes: i = the item fruit that is given a price adjustment, j = stakeholder group, k = key issue

The price of the fruit is to be adjusted higher or lower depending on the quality of the fruit, as determined by a scoring system that is acceptable to the stakeholders in each stakeholder group. The three issues of the fruit shop analogy are: (i) fruit taste, (ii) consumer satisfaction and (iii) sustainability. Each issue will correspond to a unique set of stakeholders. A hypothetical example of how the same fruit is divided three different ways, to match the three different issues, is shown in Figure 1.

The stakeholder groups for the tasting fruit are chosen based on their ability to taste fruit (j=1). Referring to the first issue in Figure 1, the first stakeholder group is responsible for tasting strawberries (k=1). They rank the strawberries according to their taste criteria. A scoring system (to be developed) is then used to give the strawberries a quantitative score. The scores are then used to adjust their prices according a protocol (to be developed). The strawberries that have the best taste and the highest score receive the highest price adjustments. Note the stakeholder groups for consumers (k=2) and sustainability experts (k=3) operate in a similar way, but with different relationships to the fruit.

Figure 1. Grouping Fruit into Stakeholder Groups (Hypothetical)